Incorporating an Integrative and Holistic Approach for Chronic Pelvic Pain Patients

Received Date: July 11, 2020 Accepted Date: July 31, 2020 Published Date: August 03, 2020

doi: 10.17303/jwhg.2020.7.303

Citation:: Lindsay Clark Donat (2020) Incorporating an Integrative and Holistic Approach for Chronic Pelvic Pain Patients. J Womens Health Gyn 7: 1-7.

Abstract

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) is one of the most common pain conditions suffered by women and can severely affect the quality of life, including physical functioning, psychological wellbeing, and interpersonal relationships. The estimated prevalence for women of reproductive ages is between 14% – 24%, and about 14% of women experience CPP during their life [1,2]. CPP syndrome in women is multi-faceted with interconnections between organ systems, musculature, fascia, and the peripheral and central nervous system. Standard treatments often have limited effectiveness. To date, there is a broad range of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) techniques that have been studied for the treatment of CPP. Therefore, it is essential for providers to be familiar with a range of treatment options that draw from conventional medicine, as well as complementary and alternative modalities.

List of abbreviations: CPP: Chronic pelvic pain; CAM: complementary and alternative medicine; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; PEA: palmitoylethanolamide

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Before the 1960s, there were few, if any, unifying theories regarding why pain persists despite injury recovery or lack of identifiable tissue damage. Melzack and Wall's Gate Control Theory is a rich and integrated theory that seeks to explain not only the physiological factors that maintain pain, but the cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and social as well [3]. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), in conjunction with appropriate medical intervention, is uniquely suited to address these factors that perpetuate CPP. CBT is a broad term for therapies that involve a focus on changing behaviors and thoughts in order to change affective states. CBT and mindfulness-based interventions have long been recognized as effective treatments for reducing chronic pain, and a recent meta-analysis suggests that there is no significant difference in outcome between either CBT or mindfulness-based interventions for these patients [4].

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and mindfulness-based interventions address an individual's pelvic pain in a variety of ways. Behaviorally, participants are taught exercises such as diaphragmatic breathing and progressive muscle relaxation, to target muscle tension and accompanying anxiety [6]. Behavioral activation strategies help patients to interrupt the chronic pain cycle, and decrease associated depression. Patients are then taught to challenge catastrophic cognitions that they may experience in response to pain, which serve to increase negative emotional states. The goal of mindfulness-based interventions is not changing, but rather acceptance. Paradoxically, once patients learn to allow unpleasant sensations to come and go rather than fighting them, they often report decreases in pain.

Although there is limited data specific to CPP, one study found "reduced overall pain severity and pain during intercourse, increased sexual satisfaction, enhanced sexual function, and less exaggerated responses to pain", following a course of CBT [6]. A small pilot study found that women with CPP who participated in an 8-week mindfulness meditation program had improvement in daily pain scores, physical function, mental health, and social function [7]. One limitation of CBT and mindfulness are the time-intensive nature of the care. A 2019 study demonstrated the effectiveness of a short-term CBT intervention delivered in a primary care setting [5]. Having a psychotherapist who is trained to deliver these services alongside physicians providing necessary medical treatment to patients should move towards becoming the standard of care.

The Role of Diet

Dietary modifications have long been recommended for the management of specific pelvic pain conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS). For example, in IBS, dietary modifications include the elimination of gas-producing foods, lactose avoidance, and a diet low in fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols [8-11]. Similarly, modifying one's diet and avoiding "triggers" has long been recommended as part of firstline therapy for IC/BPS, despite limited high-quality evidence supporting its efficacy [12]. Several observational studies have identified consistent pain triggers, including caffeinated beverages, artificial sweeteners, spicy foods, and alcohol, amongst others [13-14]. One prospective trial of target dietary manipulation supported the benefit of adhering to an elimination diet for the management of IC/BPS [15].

Research into the role of dietary modifications and supplements for other pelvic pain conditions, such as endometriosis and dysmenorrhea, is ongoing. A recent study of 160 women with comorbid IBS and endometriosis reported a reduction in pain after following a low FODMAP diet for four weeks [16]. Other studies have had positive results when implementing a variety of dietary interventions in endometriosis patients, including the use of a gluten-free diet, the addition of dietary supplements including vitamins, mineral salts, lactic ferments, and fish oil, and other dietary supplements including alpha-lipoic acid, palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) and myrrh [17-19]. A large prospective cohort study of reproductive-aged women found that women who consumed more than 2 servings of red meat per day had a 56% higher risk of laparoscopically-confirmed endometriosis, compared to women who had 1 or fewer servings per week [20]. This study also found an association with heme iron intake and endometriosis. While this study did not evaluate the effect of eliminating red meat from one’s diet as a way of reducing pain, it does suggest the role of diet as a modifiable factor in the development of endometriosis and endometriosis-associated pain.

Other studies have looked more generally at menstrual pain. A systematic review of dietary effects on menstrual pain suggested that diets high in fruits, vegetables, fish, and milk were associated with decreased pain [21]. Additionally, a Cochrane Review suggested that fish oil might improve menstrual pain [22]. Dietary therapy aimed at increasing antioxidants has been shown to improve nociceptive, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain associated with CPP [23]. Antioxidants such as omega-3 fatty acids have anti prostaglandin activity reducing dysmenorrhea and inflammation. It is likely that dietary modifications can benefit patients with chronic pelvic pain, however, the modifications should be tailored to the patient and their specific pain generators and symptoms.

Yoga

Yoga has been shown to be beneficial for chronic pain conditions, including CPP and dysmenorrhea [24,25]. These benefits include improvement in pain, mood, sleep, and quality of life. Several randomized and non-randomized studies looking at the effect of yoga on dysmenorrhea have shown a significant reduction in menstrual pain for those practicing yoga [26,27]. A systematic review, which included 854 women from 12 studies, demonstrated that exercise, including yoga, significantly reduced dysmenorrhea [28]. Similar outcomes have been noted in patients with general CPP. In one small trial of 16 women initiating a yoga program aimed to reduce chronic pelvic pain, there was a significant decrease in pain scores and improvement in the quality of life scores following a 6-week yoga practice [29]. Similarly, in a randomized control trial of 60 women evaluating the effect of yoga on chronic pelvic pain, patients who were randomized to the experimental group reported improved pain and quality of life scores after completing an 8-week yoga program [30]. To date, there is a growing body of literature supporting the role yoga practice may play as a complementary treatment for CPP. Based on this data, the slow introduction of gentle yoga practice can be recommended to most patients experiencing CPP.

Craniosacral Therapy

As compared to other CAM therapies, there is a paucity of data on craniosacral therapy (CST) for the management of CPP. Craniosacral therapy is derived from osteopathic manipulative treatments and uses non-invasive gentile palpation to release myofascial structures in the craniosacral system [31]. The exact mechanism of the therapy is not well understood. A single study of 123 pregnant women evaluated the role of CST in the management of pelvic pain [32]. This study demonstrated a mild improvement in pelvic pain and functional status. While this therapy has a favorable safety profile, further studies are needed to further elucidate the role of this therapy in the management of CPP.

Posterior Tibial Nerve Stimulation

Posterior Tibial Nerve Stimulation (PTNS), a procedure where an acupuncture needle is placed behind the ankle and electrical stimulation is administered to the posterior tibial nerve, was initially proposed for overactive bladder syndrome [33]. Treatments are generally administered as 30-minute sessions once a week for 12 weeks. While the mechanism of actions is not clearly understood, it has been studied for the management of CPP refractory to other treatments [34]. One small randomized-controlled trial looking at women with a general diagnosis of CPP demonstrated an improvement in both pain and quality of life scores after completing 12 weeks of PTNS [35]. Several observational studies of women with general CPP have demonstrated similar findings, with improvement in pain scores and quality of life scores in 40-100% of patients [36-38]. In contrast, one study of 14 patients with intractable interstitial cystitis/ bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) demonstrated no benefit for PTNS [39]. Based on the available data, PTNS is a safe option for patients with CPP and can be considered in patients who do not respond to other treatments.

Acupuncture

Traditional Chinese medicine holds that menstrual pain comes from the stagnation of blood or Qi around the uterus [40]. Conceptually, the theory behind acupuncture and CPP is that acupuncture can increase blood flow to organs and tissues, and ultimately this will help alleviate pain. One example of acupuncture helping with pelvic pain is an investigative study that found auricular acupuncture significantly reduced short-term pain in patients with severe dysmenorrhea due to endometriosis [41]. One systematic review showed that acupoint stimulation could have good short-term effects on primary dysmenorrhea [42]. Limited data exist on the use of acupuncture for the management of CPP, however current literature supports a benefit in the use of acupuncture for dysmenorrhea. More research is required to further explore both the short-term and long-term effects of acupuncture to help symptoms of pelvic pain.

Homeopathic Medication for Pelvic Floor Trigger Point Injections and Peripheral Nerve Blocks

Traumeel is a fixed combination of diluted plant and mineral extracts, which aims to decrease inflammation and promote healing. Traumeelis currently used to treat pain and inflammation during acute musculoskeletal injuries [43]. It can be used in the form of tablets, drops, injection solution, ointment, and gel. One study looked at sixteen patients with biopsy-confirmed Endometriosis who underwent a series of ultrasound-guided pelvic floor trigger-point injections and peripheral nerve hydro dissection using the homeopathic medication traumeel in combination with lidocaine [44]. This study showed the trigger-point injections and peripheral nerve hydro dissection was effective at relieving pain associated with endometriosis and improving overall pelvic function, particularly in relation to intercourse, working, and sleeping. Given the small sample size, further research is necessary to study this unique protocol.

Conclusion

The use of CAM continues to increase, especially among those with unmet medical needs [45]. Given the limitations in, both the efficacy and side effect profile in standard treatment options, CAM and integrative medicine options should be considered to help improve pain and function for women with CPP. More high-quality studies investigating the effectiveness of CAM therapies in the treatment of CPP are needed to help guide providers in caring for this complex group of patients.

- Romão AP, Gorayeb R, Romão GS, et al. (2009) High levels of anxiety and depression have a negative effect on the quality of life of women with chronic pelvic pain. Int J Clin Pract 63: 707‐711.

- Banerjee S, Farrell RJ, Lembo T (2001) Gastroenterological causes of pelvic pain. World J Urol 19: 166‐172.

- Melzack R, Wall PD (1965) Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 150: 971‐979.

- Khoo EL, Small R, Cheng W, et al. (2019) Comparative evaluation of group-based mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment and management of chronic pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Healthn22: 26‐35.

- Beehler GP, Murphy JL, King PR, et al. (2019) Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy For Chronic Pain: Results From a Clinical Demonstration Project in Primary Care Behavioral Health. Clin J Pain 35: 809‐817.

- Bonnema R, McNamara M, Harsh J, Hopkins E (2018) Primary care management of chronic pelvic pain in women. Cleve Clin J Med 85: 215‐223.

- Fox SD, Flynn E, Allen RH (2011) Mindfulness meditation for women with chronic pelvic pain: a pilot study. J Reprod Med 56: 158‐162.

- Böhn L, Störsrud S, Liljebo T, et al. (2015) Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 149: 1399‐1407.

- Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, Gibson PR (2008) Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 6: 765‐771.

- Yang J, Deng Y, Chu H, et al. (2013) Prevalence and presentation of lactose intolerance and effects on dairy product intake in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 11: 262‐268.e1.

- Zhu Y, Zheng X, Cong Y, et al. (2013) Bloating and distention in irritable bowel syndrome: the role of gas production and visceral sensation after lactose ingestion in a population with lactase deficiency. Am J Gastroenterol 108: 1516‐1525.

- Friedlander JI, Shorter B, Moldwin RM (2012) Diet and its role in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) and comorbid conditions. BJU Int. 109:1584‐1591.

- Bassaly R, Downes K, Hart S (2011) Dietary consumption triggers in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome patients. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 17: 36‐39.

- Shorter B, Lesser M, Moldwin RM, Kushner L (2007) Effect of comestibles on symptoms of interstitial cystitis. J Urol 178:145‐152.

- Oh-Oka H (2017) Clinical Efficacy of 1-Year Intensive Systematic Dietary Manipulation as Complementary and Alternative Medicine Therapies on Female Patients With Interstitial Cystitis/Bladder Pain Syndrome. Urology 106: 50‐54.

- Moore JS, Gibson PR, Perry RE, Burgell RE (2017) Endometriosis in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: Specific symptomatic and demographic profile, and response to the low FODMAP diet. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynecol 57: 201‐205.

- Marziali M, Venza M, Lazzaro S, Lazzaro A, Micossi C, Stolfi VM (2012) Gluten-free diet: a new strategy for management of painful endometriosis related symptoms?.Minerva Chir. 67: 499‐504.

- Sesti F, Pietropolli A, Capozzolo T, et al. (2007) Hormonal suppression treatment or dietary therapy versus placebo in the control of painful symptoms after conservative surgery for endometriosis stage III-IV. A randomized comparative trial. FertilSteril 88: 1541‐1547.

- De Leo V, Cagnacci A, Cappelli V, Biasioli A, Leonardi D, Seracchioli R (2019) Role of a natural integrator based on lipoic acid, palmitoylethanolamide and myrrh in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis. Minerva Ginecol 71: 191‐195.

- Yamamoto A, Harris HR, Vitonis AF, Chavarro JE, Missmer SA (2018) A prospective cohort study of meat and fish consumption and endometriosis risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol 219: 178. e1‐178.e10.

- Bajalan Z, Alimoradi Z, Moafi F (2019) Nutrition as a Potential Factor of Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Gynecol Obstet Invest 84: 209‐224.

- Pattanittum P, Kunyanone N, Brown J, et al. (2016) Dietary supplements for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3: CD002124.

- Sesti F, Capozzolo T, Pietropolli A, Collalti M, Bollea MR, Piccione E (2011) Dietary therapy: a new strategy for management of chronic pelvic pain. Nutr Res Rev. 24: 31‐38.

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH (2017) Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4: CD011279.

- Wieland LS, Skoetz N, Pilkington K, Vempati R, D'Adamo CR, Berman BM (2017)Yoga treatment for chronic non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1:CD010671.

- Rakhshaee Z (2011) Effect of three yoga poses (cobra, cat and fish poses) in women with primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 24: 192‐196.

- Yang NY, Kim SD (2016) Effects of a Yoga Program on Menstrual Cramps and Menstrual Distress in Undergraduate Students with Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Altern Complement Med. 22: 732‐738.

- Armour M, Ee CC, Naidoo D, et al. (2019) Exercise for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 9: CD004142.

- Huang AJ, Rowen TS, Abercrombie P, et al. (2017) Development and Feasibility of a Group-Based Therapeutic Yoga Program for Women with Chronic Pelvic Pain. Pain Med. 18: 1864‐1872.

- Saxena R, Gupta M, Shankar N, Jain S, Saxena A (2017) Effects of yogic intervention on pain scores and quality of life in females with chronic pelvic pain. Int J Yoga 10: 9‐15.

- Haller H, Lauche R, Sundberg T, Dobos G, Cramer H (2019) Craniosacral therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21: 1.

- Elden H, Östgaard HC, Glantz A, Marciniak P, Linnér AC, Olsén MF (2013) Effects of craniosacral therapy as an adjunct to standard treatment for pelvic girdle pain in pregnant women: a multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 92: 775‐782.

- Roy H, Offiah I, Dua A (2018) Neuromodulation for Pelvic and Urogenital Pain. Brain Sci. 8:180.

- Gaziev G, Topazio L, Iacovelli V, et al. (2013) Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation (PTNS) efficacy in the treatment of lower urinary tract dysfunctions: a systematic review. BMC Urol. 13: 61.

- Istek A, GungorUgurlucan F, Yasa C, Gokyildiz S, Yalcin O (2014) Randomized trial of long-term effects of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation on chronic pelvic pain. Arch Gynecol Obstet 290: 291‐298.

- van Balken MR, Vandoninck V, Messelink BJ, et al. (2003) Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation as neuromodulation treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol 43: 158‐163.

- Kim SW, Paick JS, Ku JH (2007) Percutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a preliminary study. Urol Int. 78: 58‐62.

- Gokyildiz S, KizilkayaBeji N, Yalcin O, Istek A (2012) Effects of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation therapy on chronic pelvic pain. Gynecol Obstet Invest 73: 99‐105.

- Zhao J, Nordling J (2004) Posterior tibial nerve stimulation in patients with intractable interstitial cystitis. BJU Int. 94: 101‐104.

- Wang SM, Kain ZN, White P (2008) Acupuncture analgesia: I. The scientific basis. AnesthAnalg106: 602‐610.

- Zhu X, Hamilton KD, Mc Nicol ED (2011) Acupuncture for pain in endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD007864.

- Chung YC, Chen HH, Yeh ML (2012) Acupoint stimulation intervention for people with primary dysmenorrhea: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Complement Ther Med 20: 353‐363.

- Schneider C (2011) Traumeel - an emerging option to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the management of acute musculoskeletal injuries. Int J Gen Med 4: 225‐234.

- Plavnik K, Tenaglia A, Hill C, Ahmed T, Shrikhande A (2019) A Novel, Non-opioid Treatment for Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women with Previously Treated Endometriosis Utilizing Pelvic-Floor Musculature Trigger-Point Injections and Peripheral Nerve Hydrodissection. American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1–8.

- Abercrombie PD, Learman LA (2012) Providing holistic care for women with chronic pelvic pain. J ObstetGynecol Neonatal Nurs 41: 668‐679.

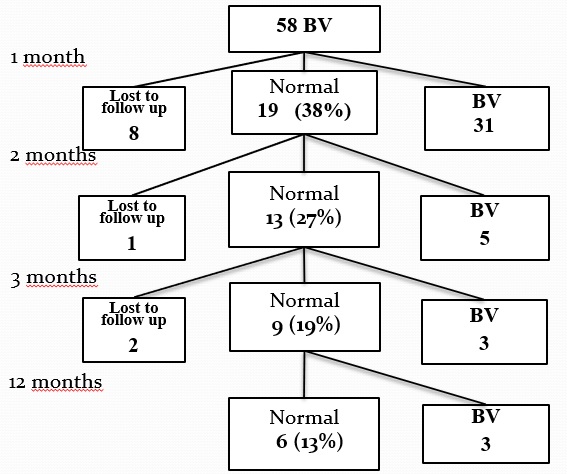

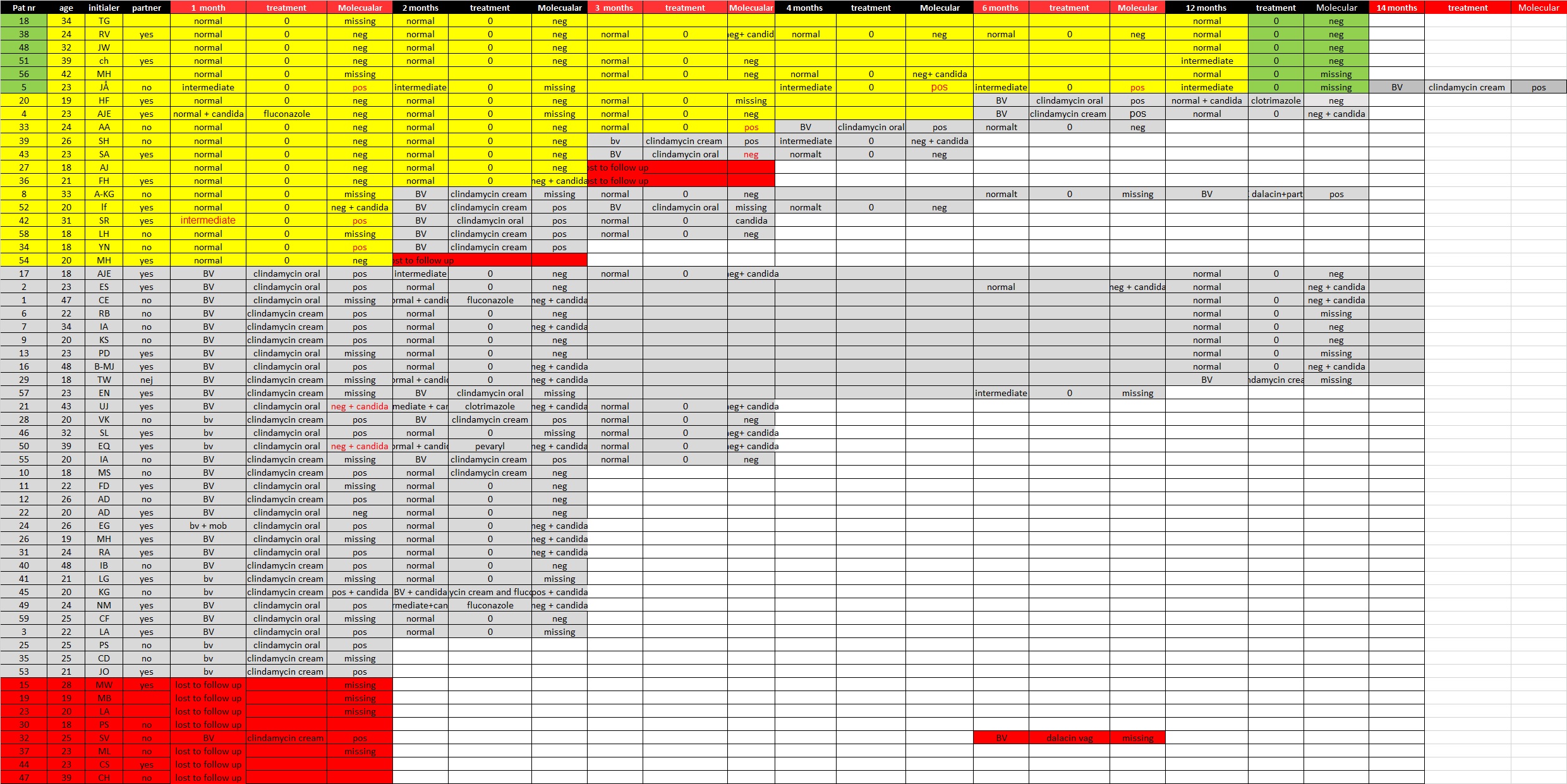

Tables at a glance